Critical Digital Praxis in Education

A discussion of Rebecca Kelly's "Mobile assisted third space (MATS) in the margins"

Rebecca Kelly’s (2020) "Mobile assisted third space (MATS) in the margins” discusses the intersections of Third Space Theory and mobile learning pedagogy, ultimately revealing the potential of mobile learning to create spaces that disrupt power structures, increase collaboration and agency, and promote transferability. Kelly first describes the philosophical underpinnings of Third Space Theory, referencing three key theorists: Edward Soja, Homi K. Bhabha, and Ray Oldenbug. At the center of Third Space Theory is a reimagining of the notion of time and space, but each theorist situates their own nuanced understanding, with Soja (1996) describing space as a process of interactions, Bhabha (1994) as a process of hybridity (a synthesis of formal and informal cultures), and Oldenburg (1989) as informal spaces “inherent to identity formation, democratic practice, and civil engagement” (Kelly 2020).

Intrinsic to Third Space Theory are Bhabha’s concept of “hybridity” and Soja and Oldenburg’s concept of “Thirding.” Bhabha’s “hybridity” asks us to challenge thought processes that rest on binary concepts; “hybrid understandings and enactments are created when binaries are challenged and new possibilities and spaces for meaning-making are created” (Kelly 2020). In a similar vein, Soja’s concept of “thirding” asks us to “set aside demands to make an either/or choice and contemplate instead the possibility of a both/and also logic” (Kelly 2020). Oldenburg conceptualizes “thirding” as “a site for identity creation and socio-political regeneration” (Kelly 2020). All in all, “third space” is a collective space, one in which dominant and marginalized communities synthesize to create a new discourse. Kelly (2020) explains, “Third Spaces become hybrid learning spaces in which students’ linguistic and cultural forms, styles, artifacts, goals or ways of relating all interrelate and combine to transform the official linguistic and cultural forms of the school, teacher or classroom into an individualized and internalized experience.”

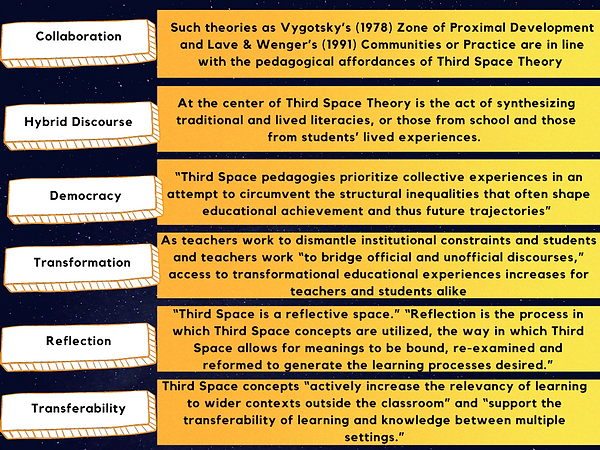

The following pedagogical qualities are inherent to Third Space Theory:

Kelly finally goes on to describe how the concepts inherent in Third Space Theory have particular potential to be actualized through mobile learning. Mobile learning itself destabilizes traditional notions of how and when learning occurs, creates spaces that are formal and informal, and widens capacity for collaboration and contexts. Of note, Kelly (2020) mentions the importance of online social networking sites (SNSs) as functioning as Third Spaces of socio-educational construction that bridge academic and social discourses. Guerra-Nunez's (2017) study of Latin American students in U.S. classrooms revealed that integrated mobile learning “redistributed power” in the classroom, not only between students and teachers but between students and students, which “increased motivation and engagement amongst students from all backgrounds” (Kelly 2020).

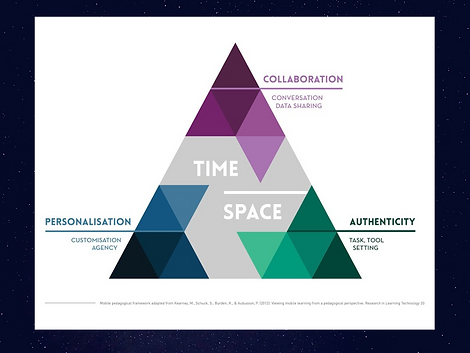

Third Space Theory is compatible with mobile learning pedagogy such as the iPAC Framework, which centers on the concept of time and space to emphasize the “innovative uses of the temporal and spatial dimensions of learning” to enable collaboration, personalization, and authenticity as core characteristics (Kelly 2020). Collaboration enables hybrid discourses and interactions with a range of people and environments. Personalization honors the individual learning experience and increases learner agency. Authenticity enables learning to occur in realistic contexts, which makes it more transferable "between classroom space and real life spaces” (Kelly 2020).

Below is a popular image illustrating the iPAC Framework.

Kelly ends her article on the use of MATS for a Food for UsLinks to an external site. pilot project that enabled education around sustainable farming practices for marginalized rural farmers in Western and East Cape areas of South Africa. Kelly (2020) explains how the use of an app enabled interaction and engagement among diverse groups of people that were otherwise very socially isolated: “Participating farmers were able to send messages and posts to other farmers with expertise in different areas of agriculture but also to make contact with businesses that could utilize their produce such as shops, market stall holders and food outlets (Food for Us, 2019).“ Participant interactions via the Food for Us app created agency as they tailored their participation to their needs, and researchers observed that farmer practices began to change and transform as a result (Kelly 2020). Of note, these small-scale farmers learned how to access local buyers they otherwise did not know existed and secured higher prices than they received from large food corporations. “The app,” Kelly (2020) explains, “supported a disruption of existing value chains which previously placed the small-scale rural farmers produce at the lowest end of this chain.”

While reading this article, I imagined how useful mobile learning could be to create informal spaces that blend with the formal atmosphere of education, and how this could be leveraged as a tool not only for socialization but for co-creating curriculum and designing personalized learning projects. It also made me think about how I would need to reimagine how I assess student learning. I was also intrigued by how mobile learning is used outside of academia, and how useful it can be to broaden access to education on a global level. For instance, Funzi is a company that offers free education to refugees. Their courses are completely accessible on all mobile devices (not just smart phones). The founders of this company wrote the essay “Combining Robust Technology and Gamified Learning to Democratize Access to Growth Mindset” which is in the collection Critical Mobile Pedagogy. Also in this collection is Witthaus and Ryan’s (2020) “Supported mobile earning in the ‘Third Spaces’ between non-formal and formal education for displaced people” which compares how three academic programs focused on mobile access for refugees enact third spaces: Bridge Programmes in Scotland, InZone at the University of Geneva, and the online learning platform Kiron. I was fascinated by the work of these companies and the impact they are making on a global level by leveraging mobile learning and the accessibility it enables.

Overall, the potential of mobile learning, its relative underuse in academia, and its ability to increase access to education on a global level, is an intriguing area of study. It begs the question: What should future definitions and designs of learning be?

Reference

Kelly, R. (2020). Mobile assisted third space (MATS) in the margins: A tool for social justice and democracy. Critical mobile pedagogy: Cases of digital technologies and learners at the margins (1st ed.). Traxler, J., & Crompton, H. (Eds.). Routledge. https://doi-org.libproxy.uwyo.edu/10.4324/9780429261572